‘Need to know’ for wind farm procedure choice

On 1 January, 2022, the Environmental and Planning Act (Omgevingswet) will come into force according to the official schedule, although according to news in recent days, it seems to be heading for another postponement… However, as long as that postponement has not yet been formally announced, we can assume 1 January, 2022. And with three quarters of a year to go, it’s becoming increasingly important for early stage projects to determine whether the procedures for a (wind) project will still fall under current legislation or under the new Environmental and Planning Act. But what procedural choices will there be under the Environmental and Planning Act? Because if a project falls under the effect of the new law, that should be anticipated in the preparations. From approximately this summer, this is something that we should start to think about. That is, what drives the momentum in determining whether a project falls under the old or the new law?

In recent months I, together with Erwin Noordover of NewGround Law, have been able to give various courses to business partners regarding the development of (in particular) wind projects in relation to the Environmental and Planning Act. In addition, we have seen a number of concrete cases. The Environmental and Planning Act is generally said to be policy neutral to a large extent. But when you dive into the depths of the law while preparing for a course and search for answers to concrete questions, it turns out that things are changing. Such changes do have an impact on the development of wind projects and the procedural choices that have to be made. I would like to share, in lay terms, an important observation that we made recently. Please note: this only concerns a limited part of the total Environmental and Planning Act. But it is a ‘need to know’ in terms of the choice of procedure for the development of a wind farm.

The momentum of the Environmental and Planning Act

First of all, it’s important to know when a procedure falls under the old law or the new law, i.e. the momentum. The Implementation Act Environmental and Planning Actregulates, among other things, the transition from old legislation to the new law. Current law continues to apply to applications for an environmental permit (whether or not it deviates from the zoning plan) submitted before 1 January 2022, or when a zoning plan or, for example, an integration plan has been made available for inspection before 1 January 2022. Until the decision is final, the decision-making will be handled under the current law, even if the new law has already entered into force. I suspect that this will still lead to the necessary applications for an environmental permit before 12 noon on 31 December next. This may not be such a bad idea for projects that are already fairly advanced in their preparation…. But more on that later!

Relevant procedures in current practice and changes due to Environmental and Planning Act

Under current legislation, there are actually two main uses for the (planning) procedure for the construction of a wind project: an environmental permit deviation from the applicable zoning plan, or a revision of the applicable zoning plan (or an integration plan when the national or provincial authorities are competent). Under the Environmental and Planning Act, the zoning plan is replaced by the municipal environmental plan. An environmental plan oversees the entire physical living environment and will therefore include rules for things like felling, welfare and environmental values (environmental rules). Central government and province will also receive a new toolunder the Environmental and Planning Act: the project decision as a replacement for the integration plan. A project decision changes the municipal environmental plan and is given its own new (more extensive) procedure, leading to an appeal in one instance and accelerated processing at the Administrative Jurisdiction Division of the Council of State. In the case of the central government and the province, the project decision may also immediately contain the required environmental permit(s).

In addition, the Environmental and Planning Act includes the environmental permit. For projects that do not fit into the applicable environmental plan, the environmental plan activity can become part of the environmental permit. The latter is actually the component deviation from the environmental plan and therefore comparable to the current deviation from the zoning plan in the environmental permit.

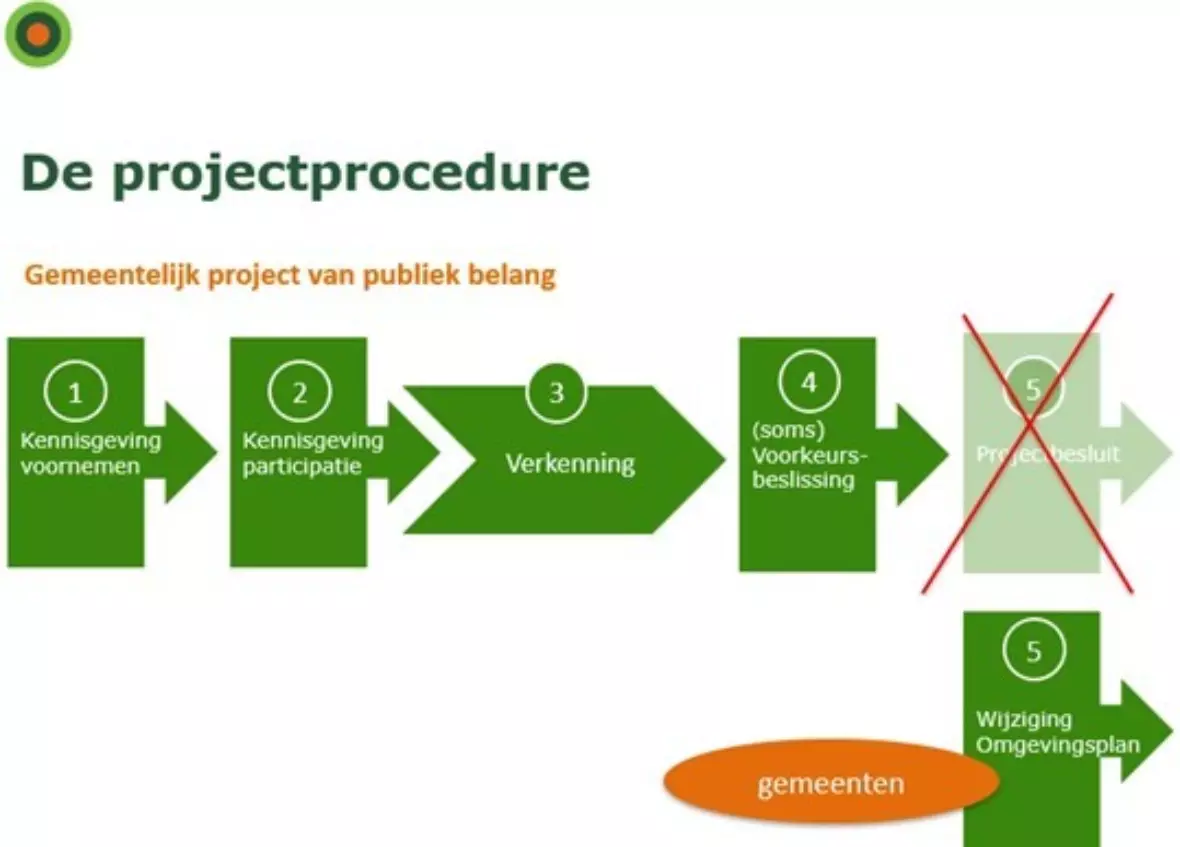

According to the Environmental and Planning Act, the municipality can also choose to follow the ‘project procedure’ for a municipal project of public interest (Article 5.55 Environmental and Planning Act). The project procedure is the procedure that forms part of the central government’s project decision and the province to arrive at a project decision. For the municipality, this only results in ‘the inclusion of rules in the environmental plan that are aimed at the implementation and operation or maintenance of a project of public interest’. In other words: the project procedure at the level of the municipality always leads to an amendment to an environmental plan and never to an environmental permit for deviation from the environmental plan. In addition to the amendment of an environmental plan, an environmental permit must always be applied for separately for other activities in the development of the project. Required environmental permits for the implementation of the project can be prepared in a coordinated manner with the environmental plan change. The coordination arrangement can also be applied to subsequent implementing decisions. The advantage for municipalities of following the project procedure is also an accelerated handling by the Administrative Jurisdiction Division of the Council of State, just as with the project decision.

So much for a brief overview of instruments under the current and new law. It doesn’t seem to be changing all that much from the current options, except that the municipality can also opt for the project procedure as an extra procedure/instrument. However, there is something unique going on for wind projects that will severely limit the choice of procedure. In fact, in almost all cases there is no procedural choice at all under the Environmental and Planning Act for the construction of wind farms. I will explain how that works below.

Amendment of the Electricity Act 1998 through the Implementation Act

Recently, on 11 February, 2021, the Implementation Act Environmental and Planning Act was passed by the Senate. This makes it final, with only the date it comes into force to be determined. The Implementation Act revises a large number of other laws with the introduction of the Environmental and Planning Act. Who the competent authority is for a wind farm of a certain size is now regulated in the Electricity Act 1998. Under the Environmental and Planning Act, this will remain in the Electricity Act. The Environmental and Planning Act Implementation Act only revises relevant parts of the Electricity Act 1998 in order to synchronise them with the Environmental and Planning Act. The now known Articles 9b to 9g Electricity Act 1998, including the division of powers to decide on wind farms, will be replaced by new Articles 9b and 9c by the Implementation Act. The classification in production capacity remains the same: wind farms with a size of 5 to 100 MW are in principle a provincial competence, and for wind farms of more than 100 MW the power to decide lies in principle with the national government. The central government (the minister) or the province (provincial executive) can place the authority to decide on a wind farm for which they are competent to the municipality (for the province if the minimum realisation standard has not yet been met). Therefore, not really anything new so far, except that the provincial executive will be empowered instead of provincial councils. The difference with current legal practice is really in the tail-end. In order to transfer the authority to the municipality, the Minister/Provincial Executive will not take a project decision if, in their opinion, the project “can be carried out in accordance with Article 5.55 of the Environmental and Planning Act and with the agreement of the competent administrative body of the municipality where the project is carried out.” This means that the municipal council must (in advance?) agree to take over the authority, but that they are also bound by the application of the project procedure via Article 5.55 of the Environmental and Planning Act. The latter means that for all wind projects of more than 5 MW (which actually includes almost all projects involving two or more wind turbines) a project procedure must be followed.

It remains to be seen what this will mean for the wind sector in practice. To be honest, I suspect that municipalities are not currently preparing to use the project procedure, but as they approach 1 January 2022, will mainly focus on having the environmental plan, the environmental permit granting and the digital system in order. Municipalities already have their hands full with these things. The Environmental and Planning Act itself gives the project procedure as a choice option, so there is no immediate reason for municipalities to be already preparing for this. But through the back door of the amendment to the Electricity Act, municipalities can be required to apply the project procedure for wind projects of 5 MW and more, if they want to take on that project at least. To be honest, I suspect that the willingness on the part of municipalities to cooperate in wind projects (at least to take over the authority) will be smaller once the Environmental and Planning Act comes into force than is currently the case. I am talking specifically about procedural considerations. Wind projects are generally already politically sensitive, so the question is whether a city council will formally agree in advance to take over the power to decide on a wind project and then also be bound by the mandatory procedure which they may not yet be prepared for. I therefore think that under the Environmental and Planning Act, to a greater degree than at present, it will be up to the provinces to make wind projects procedurally possible via the project decision. In practice, this seems to be a bit contradictory to the so-called ‘subsidiarity principle’ of the law: ‘decentralised, unless’.

What is wisdom?

But the biggest question is of course how to proceed with projects that are in preparation. It is important to consult with the relevant competent authorities to see whether the project will still fall under the current law or the new law and to discuss the consequences and to agree who will act as the competent authority and also determine what is required for that. In any case, a project that will follow a project procedure in accordance with prescribed steps of intention, exploration and preference decision (Articles 5.47 to 5.50 Environmental and Planning Act) must be prepared, regardless of whether the national, provincial or municipal authorities are the competent authorities. These steps may also have to be Environmental and Planning Act compliant this year if the project can fall under the Environmental and Planning Act. For projects that are far enough to submit an environmental permit (with deviation from the zoning plan), it is, in my opinion, advisable to submit them at least before 1 January 2022 so that it can still be handled under the old law. The ambiguities of the new law can thus be sidelined. If a zoning plan procedure is to be followed for a project, a design must be made available for inspection before 1 January 2022. I do wonder whether municipalities still have time to start a new zoning plan procedure after the summer, since they will then be in the middle of preparing the new law. Perhaps the choice to submit an environmental permit with deviation from the zoning plan will then be more obvious because the initiator can then influence the momentum by submitting and is not dependent on the municipality.

Finally

I am curious about what other surprises the Environmental and Planning Act has in store. As the entry into force is getting closer, the questions also become more concrete, we dive deeper into them and the details of the law become more visible. Although not much is changing overall, the sting may be in the tail. Perhaps there will be more ‘fine print’ to share in the next blog!